Installation views of Hangama Amiri: Reminiscences Photography: Reinis Lismanis

Hangama Amiri: Reminiscences

August 25 — September 24 2022

At Union Pacific gallery, London

Exhibition essay by Sarah Burney

Hangama Amiri has employed an architectural splitscreen to take us inside the story of a separation. Combining the visual vocabulary of history painting with the skills and materials of a couturier Amiri is reminiscing on her childhood by exploring, in cloth, the photographs her parents exchanged in the years following the family’s exodus from Afghanistan — nine long years during which her father, in an effort to provide for and secure a path to immigration for his family, moved to Norway and then Denmark, while her mother, shuttling between refugee housing, reared Amiri and her three siblings in Tajikistan.

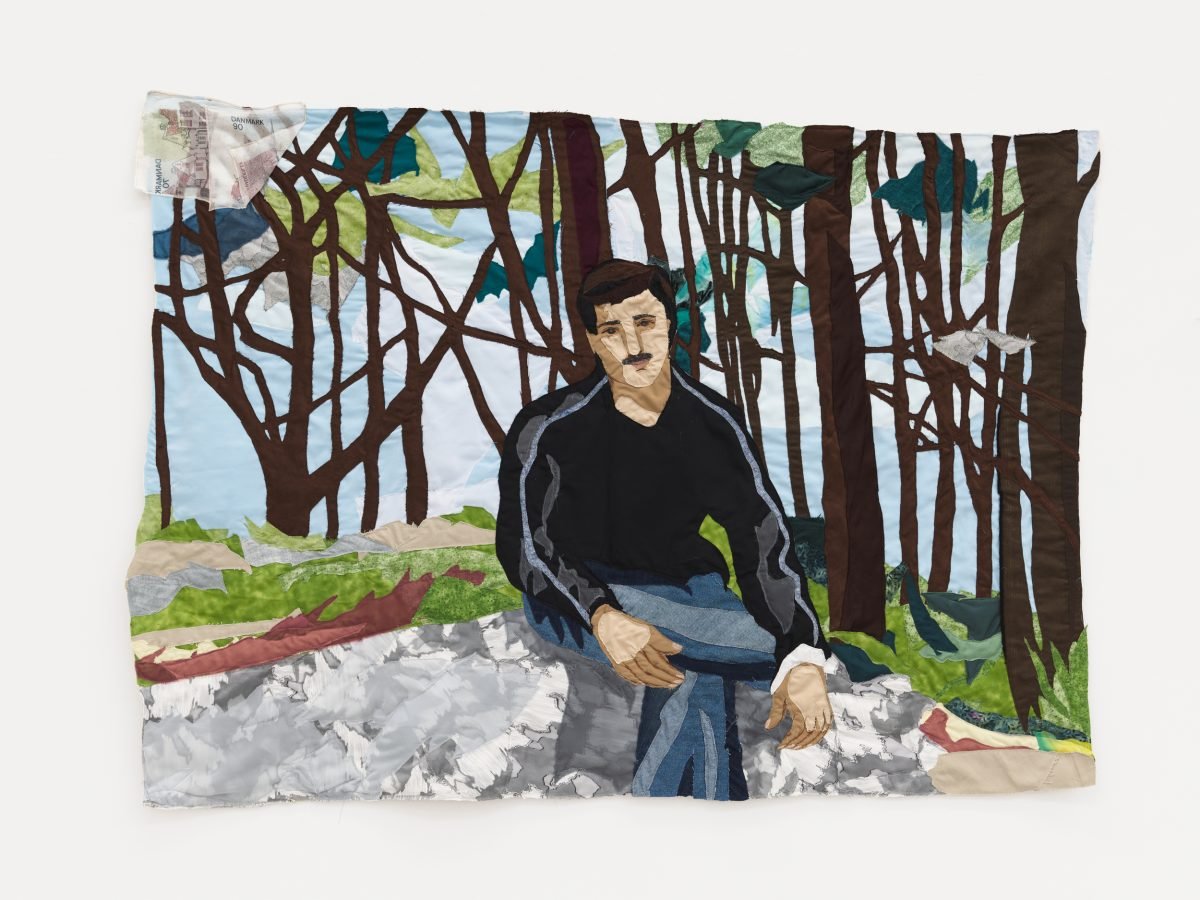

Hangama Amiri, Man Resting in the Park, 2022, Muslin, cotton, polyester, chiffon, denim, sued, silk, inkjet print on silk-chiffon, and found fabrics / mussolina, 106.68 × 152.40 cm

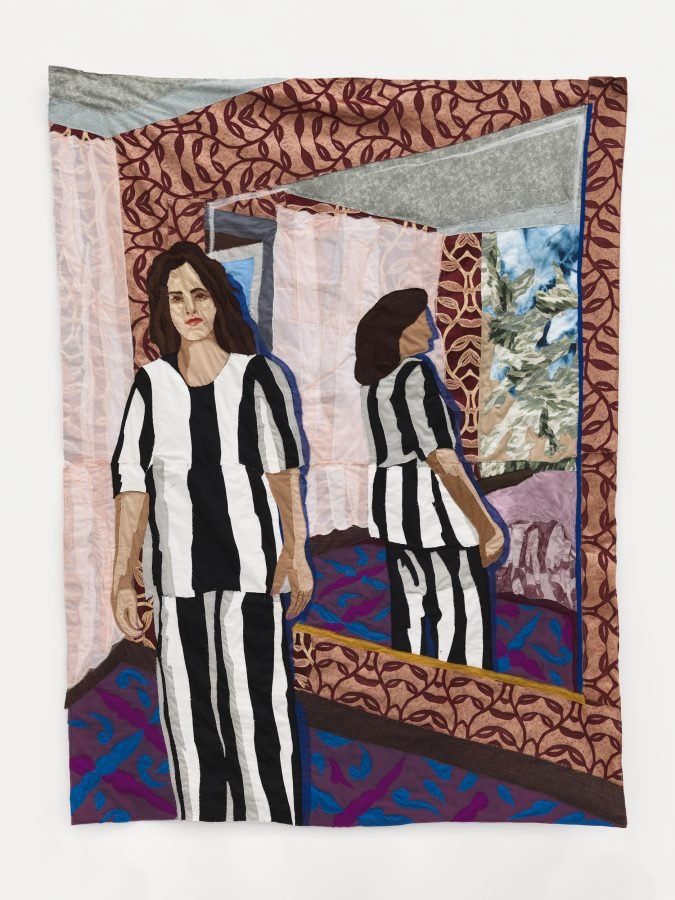

The top floor of the gallery is a repository of her father’s dispatches: plein air self-portraits documenting his life. We see him sitting amongst tulips, in front of a grocery store, about to fell a tree, and resting in a park. Downstairs, we are surrounded by the images her mother shared: self-portraits in which she is always elegantly dressed — she poses alongside a wall of built-in shelves, in a park, with her youngest son, and in front of a mirror. Amiri complicates the cross-cut; a still life of an Eid feast, sent by her mother, is on the first floor and new visuals, imagined by the daughter, appear alongside those of her parents.

Hangama Amiri, Portrait of a Woman with her Son, 2022, Muslin, cotton, polyester, dyed fabric, velvet, chiffon, sued, embroidery pattern, silk, and found fabrics, 172.72 × 121.92 cm

Each piece is a kaleidoscopic rhapsody of texture and color. Working in her signature fabric appliqué process, Amiri hand cuts shapes in a panoply of different fabrics and sews them onto a base textile, effectively collaging an image together with patches and thread. With a painterly approach to fabric, she layers multiple chiffons to achieve precise colors, uses both the front and muted reverse of printed fabrics, and incorporates fabrics that mimic the tactility of their subject: smooth and silky velvets for tulips, shimmering sequins for the straps on her father’s work gloves and ornate laces for her mother’s clothes. Amiri has expanded her palette for this new body of work through her use of historic wallpaper and bespoke printed textiles. These new materials allow hard-to-find patterns and reproductions of paper ephemera and photographic images into her rich visual lexicon.

Detail from Man with Tulips, 2022

Detail from Eid, 2022

Yet, Amiri is not just creating beautiful fabric pastiches of her parents' photographs. She is fusing archive with memory. Working as a curator she has selected ten images from the multitudes they shared over their long separation, spliced new images amongst their correspondence, and refracted details through her own nostalgia. She intentionally blurs identifying details through her titles. Man with Tulips could have been Babaa with Tulips but Amiri doesn’t directly disclose her relationship to her subjects or name them. In keeping her subjects anonymous she has created space for others to see themselves, to imagine their own narratives, and allowed herself some distance. In her work we are not just looking at a couple, but how a child remembered a couple and how she is looking at them anew though older eyes.

Hangama Amiri, Man with Tulips, 2022, Muslin, cotton, polyester, dyed fabric, velvet, chiffon, inkjet print on silk-chiffon, silk, and found fabrics, 175.26 × 196.85 cm

A collage over an old Norwegian stamp expands the idea of cornucopias: the European horn of fruits alongside images of the dried fruit and nuts her mother would send her father: a combined cultural memory of food, the most nostalgic of items. Shoe-rack is an image from the artist’s memory: her mother’s fancy shoes, a proxy for the joy she remembers her mother took in dressing up.

Hangama Amiri, Still-Life with Dried Fruits, 2022, Muslin, cotton and inkjet print on silk-chiffon, 31.75 × 60.96 cm

Hangama Amiri, Shoe-rack, 2022, Muslin, cotton, polyester, velvet, chiffon, wallpaper, sued, and found fabrics, 78.74 × 109.22 cm

Amiri meditates on the dialogue between her parents' visuals, in the unspoken declarations each partner was making. Her father’s sun-filled images were a promise to his wife of a better future in peaceful Europe. Her mother’s soignée portraits and abundant still-life, a reassurance that she and the children were safe, joyful, and living well. Amiri celebrates the resilience of her parents’ partnership, yet she is also picking at the tensions within their narratives. There were omissions within their pictorial communications that the artist underscores through her selection. Her father, who lived in crowded communal refugee housing, rarely sent home photographs of his living space. Her mother usually posed in their home. In Europe, like many migrants, her father worked for cash at tulip farms. A demanding, labor intensive job that was far removed from his professional life in Afghanistan — a change in identity that was never resented or begrudged; he posed in tulip fields for his family. In splitting her parents’ images across two floors Amiri uses the gallery’s architecture to represent their physical separation, underscoring the distance between their realities and transforming our journey up and down the staircase into a symbolic re-enactment of their emotional labor to stay coupled.

While deeply personal, Amiri's lush tableaus are also fascinating period pieces speckled with details that capture the extraordinary culture that emerged at the confluence of Afghan and Tajik communities in the late 1990s. She has preserved how families, like hers, celebrated, what entertained them, what their homes looked like, and perhaps most significantly, how they wanted to remember themselves. These lifestyle details, while educational to most, will transfix those of us who recognize our childhood in Amiri’s work.

Hangama Amiri, Eid, 2022, Muslin, cotton, polyester, dyed fabric, velvet, chiffon, wallpaper, nylon tulle, ikat-print, inkjet print on silk-chiffon, sued, paper, silk, and found fabrics, 142.24 × 106.68 cm

Eid captures not just what an Eid feast included (soft drinks, cake, fresh oranges, dried fruits, nuts, Afghan-cookies, and pastries), but how it was consumed, seated on the floor from a crisp white sheet. Downstairs, Bollywood superstars Hrithik Roshan and Kareena Kapoor are immortalized on the television screen behind her mother in Portrait of a Woman in White Salwar Kameez and reproductions of Bollywood postcards are printed on chiffon, and tucked into the corners of a mirror — a nod to her mother’s sartorial inspiration, the hours of joy these movies provided her, and Bollywood’s reach beyond India.

Hangama Amiri, Portrait of a Woman in White Salwar Kameez, 2022, Muslin, cotton, polyester, dyed fabric, velvet, chiffon, sued, leather, mesh-fabric, embroidery pattern, inkjet print on silk-chiffon, silk, and found fabrics, 182.88 × 132.08 cm

Detail from Portrait of a Woman in White Salwar Kameez, 2022

Detail from installation view.

Given the artist's source material, it is perhaps unsurprising that photography culture of Central and South Asia from the 1990s is enshrined in Amiri’s work. The formal poses, unsmiling faces, and compositional framing of each image capture the idiosyncratic habits of amateur photographers (and their subjects) of her parents’ generation. Amiri underscores her connection to photography through the swaths of roses and tulips that frame multiple textile pieces — a reference to the highly decorated photo albums that were popular at the time.

Hangama Amiri, Portrait of a Man at the Grocery Store, 2022, Muslin, cotton, polyester, dyed fabric, velvet, chiffon, mesh-fabric, inkjet print on silk-chiffon, clear vinyl, leather, sued, and found fabrics, 91.44 × 182.88 cm

Amiri’s decision to include a photograph of herself and her mother — the only original photograph in the exhibition — is a tongue-in-cheek acknowledgement of the construction of narrative her parents were attempting. Mother and daughter, in matching red shirts, are seated on boulders, amongst flowers and tropical plants while a waterfall roars behind them. It’s a fabricated image, taken at the once ubiquitous neighborhood photo studio. The plants in the foreground are biologically out of place and obviously fake, the hyperbolic waterfall is a studio backdrop. Yet this image, artificially beautified to the point of absurdity, captures the utopic ideation of a generation and how integral photography was to this pursuit, especially for a scattered diaspora.

Installation view of Hangama Amiri: Reminiscences

Detail of installation view of Hangama Amiri: Reminiscences

Pattern, which has long held Amiri’s fascination, dominates this body of work, especially in the floral carpets and wallpaper in her mother's images. In emphasizing these interior details Amiri is using pattern as a decorative element and cultural and historic signifier. She is memorializing a very specific moment in Central Asian home decor — a decorating style that borrowed more heavily from design trends in Russia than South Asia and was consequently foreign to the young Afghan family.

Hangama Amiri, Woman Before A Mirror, 2022, Muslin, cotton, polyester, dyed fabric, velvet, chiffon, silk, sued, and found fabrics, 185.42 × 135.89 cm

Interior details break the third wall downstairs. While we walk amongst her mother’s images, the lights have been dimmed, plush carpet cushions our steps, ornate wallpaper clothes the walls and a mirror reflects our own image back to us. It’s a seductive yet jarring sensory experience — soft floors and patterned walls speak to a domestic interior, a private space, not an art gallery. Our wonder and disorientation are faint echoes of the mother’s. She never expected to be standing amongst these walls and floors either — never expected to be a refugee. The homes she poses in were never hers, the government assigned pre-furnished refugee apartments reflected neither her taste or culture. Yet she holds the space — claiming it as her own and celebrating the sanctuary it provides. In enveloping us in this immersive environment and inserting our reflection alongside her mother Amiri slyly prods us to question our positioning: How certain is the safety and security we inhabit? Could we too be refugees one day? How would we bear it?

Installation view of Hangama Amiri: Reminiscences

These are timely questions that build upon Amiri’s past inquiries. In earlier bodies of work she has explored the multifaceted lives of Afghan women, constructed monumental textile installations of Kabul’s public spaces in the halcyon days before the Taliban’s return, turned to abstraction and fragmented surrealist compositions to question concepts of home, memory, identity and belonging, and memorialized objects and landmarks that connect her to her homeland from afar.

Amiri turned to the family archive to process the grief that she, like many young Afghans, has been sitting with of late. Since the Taliban’s return in 2021 she has been in mourning for the countless Afghan families splintered, like hers was, in this recent round of geopolitical roulette. Reminiscing about her extraordinary childhood has been unavoidable as she watches history repeat itself. In shifting her gaze to her parents’ experience and meditating on the ephemera of their nine year separation, Amiri has added depth, nuance and complications to our understanding of contemporary Afghan diaspora, memorialized the resilience and love of an Afghan marriage, and composed a bittersweet ballad of hope for a new generation of separated lovers.

All images courtesy of the artist and Union Pacific gallery. Photographs by Reinis Lismanis.